It has been many moons since last I communicated via these pages.

I have simply been busy relocating from one continent and setting up a new home in another. I can tell you that it was not easy to say goodbye to the beloved Afrika, the craddle of human evolution and my ancestral home.

It is also challenging planting my roots in the world's largest economy, the United States. I had to find a home, get a car and learn the ways of life in this corner of the world. On top of that, I am still trying to quickly learn my way around the city where I live and the one where I work -- there is simply no rest for the weary.

But it is all good. I am back to doing what I enjoy the most -- working as a journalist.

Before I left Afrika, I travelled deep into a remote corner of Kenya where I encountered an adventurer who has been pursuing some of the most precious stones in the continent, including Tsavorite, Ruby and others. I will tell you more about that trip in my next posting ...

Rodrique Ngowi's Photography and Cinematic Productions, compelling visual storytelling

Saturday, December 23, 2006

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

Nelson Mandela spent most of his 27 years in jail at the notorious Robben Island. I walked into the prison recently, eager for insight into conditions he must have endured in his quiet, but determined struggle to dismantle the Apartheid system in South Africa.

most of his 27 years in jail at the notorious Robben Island. I walked into the prison recently, eager for insight into conditions he must have endured in his quiet, but determined struggle to dismantle the Apartheid system in South Africa.

A walk through cold corridors in the maximum security section revealed thick iron bars on narrow windows, blankets that served as bedding for Mandela and a bucket intended to use as a toilet in the cell in which the iconic African statesman languished in this wind swept island.

The dehumanizing hardships endured by South Africans jailed in the island, located 12 kilometers from Cape Town, failed to break their spirit or extinguish the clamor for equality in the country that now boasts Africa's largest economy.

Mandela is gone from Robben Island, but the jail remains as a towering testament to

"the triumph of the human spirit, of freedom and of democracy over oppression."

Robben Island, which was used between the 17th and 20th centuries as a leper colony, military base and prison - effectively home to those deemed as undesirable to South African rulers - was declared a U.N. world heritage site in 1999.

as a leper colony, military base and prison - effectively home to those deemed as undesirable to South African rulers - was declared a U.N. world heritage site in 1999.

The trip to the island involved a ferry that carried more than 150 tourists to the historical site.

Walking from the quay, we immediately saw a building in which prisoners used to meet visiting relatives. A disused artillery gun was ahead.

A fleet of buses took us for a visit around the island, that is also home to penguins, seals, springboks, ostriches and other wildlife.

Finally, we walked into the prison, with one of the former inmates acting as a tour guide as he described condi tions in the facility during their incarceration and how prisoners in the maximum security section communicated with others using cooks to pass on messages and tennis balls stuffed with written notes.

tions in the facility during their incarceration and how prisoners in the maximum security section communicated with others using cooks to pass on messages and tennis balls stuffed with written notes.

I walked into a cell next to that of Mandela's and locked the gate for a glimpse of the outside world from the wrong side of the thick iron bars. That brief experience showed that life must have been lonely and stressful for those who spent years in that place against their will.

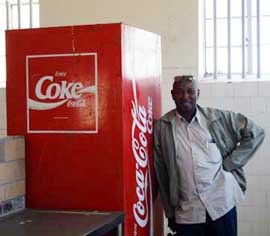

The island is now a museum and wildlife sanctuary, a place where even Coca Cola gladly calls home - as seen from the large refrigerator standing in the prison's kitchen, bearing the global brand.

most of his 27 years in jail at the notorious Robben Island. I walked into the prison recently, eager for insight into conditions he must have endured in his quiet, but determined struggle to dismantle the Apartheid system in South Africa.

most of his 27 years in jail at the notorious Robben Island. I walked into the prison recently, eager for insight into conditions he must have endured in his quiet, but determined struggle to dismantle the Apartheid system in South Africa.A walk through cold corridors in the maximum security section revealed thick iron bars on narrow windows, blankets that served as bedding for Mandela and a bucket intended to use as a toilet in the cell in which the iconic African statesman languished in this wind swept island.

The dehumanizing hardships endured by South Africans jailed in the island, located 12 kilometers from Cape Town, failed to break their spirit or extinguish the clamor for equality in the country that now boasts Africa's largest economy.

Mandela is gone from Robben Island, but the jail remains as a towering testament to

"the triumph of the human spirit, of freedom and of democracy over oppression."

Robben Island, which was used between the 17th and 20th centuries

as a leper colony, military base and prison - effectively home to those deemed as undesirable to South African rulers - was declared a U.N. world heritage site in 1999.

as a leper colony, military base and prison - effectively home to those deemed as undesirable to South African rulers - was declared a U.N. world heritage site in 1999.The trip to the island involved a ferry that carried more than 150 tourists to the historical site.

Walking from the quay, we immediately saw a building in which prisoners used to meet visiting relatives. A disused artillery gun was ahead.

A fleet of buses took us for a visit around the island, that is also home to penguins, seals, springboks, ostriches and other wildlife.

Finally, we walked into the prison, with one of the former inmates acting as a tour guide as he described condi

tions in the facility during their incarceration and how prisoners in the maximum security section communicated with others using cooks to pass on messages and tennis balls stuffed with written notes.

tions in the facility during their incarceration and how prisoners in the maximum security section communicated with others using cooks to pass on messages and tennis balls stuffed with written notes.I walked into a cell next to that of Mandela's and locked the gate for a glimpse of the outside world from the wrong side of the thick iron bars. That brief experience showed that life must have been lonely and stressful for those who spent years in that place against their will.

The island is now a museum and wildlife sanctuary, a place where even Coca Cola gladly calls home - as seen from the large refrigerator standing in the prison's kitchen, bearing the global brand.

Wednesday, March 29, 2006

For 30 years Eritreans sacrificed their lives as well as those of their sons and daughters to fight for independence from their larger neighbor, Ethiopia.

For 30 years Eritreans sacrificed their lives as well as those of their sons and daughters to fight for independence from their larger neighbor, Ethiopia.Five years after Eritrea's 1993 independence, the two countries went to war - this time over their disputed 1,000-kilometer border that was never officially demarcated during t

he decades they existed side by side.

he decades they existed side by side.The guns are silent now, but tensions remain high since the border dispute has not been resolved because Ethiopia rejected in 2003 to let an independent border commission to demarcate their border.

Ethiopia was unhappy that the commission had awarded the disputed town of Badme, the flashpoint of their 1998-2000 border war, and other territories to Eritrea. The commission was set up under the countries' 2002 peace agreement under they both agreed in advance that its border ruling will be final and binding.

Eritrea has criticized Ethiopia's attempts to overturn the ruling as attempts to shift the goal post after the rival side has scored a goal.

The Red Sea state has pressed the United Nations, the U.S., European Union and other countries to use their economic might to press Ethiopia - that receives some $1.9 billion in humanitarian and development aid annually - to respect the peace agreement and resolve the border dispute conclusively.

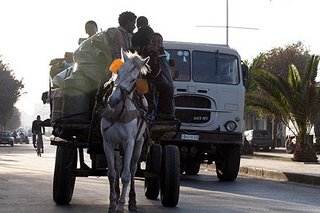

I traveled to Eritrea recently to see the impact of the unresolved border dispute on the country's economy and lives of people in the boundary, where heavily-armed militiamen from the two countries watch the movements of the other with suspicion.

I traveled by road around the mountainous nation, whose narrow Red Sea coastal plain is one of the hottest and driest places in Africa. The cooler central highlands, where the capital lies, have fertile valleys that support agriculture.

THIS IS NO SIMPLE DISPUTE

THIS IS NO SIMPLE DISPUTEThe Eritrea-Ethiopia border dispute is not a simple border dispute.

For Eritrea, the land dispute is a matter of national pride and the ultimate assertion of independence. Many Ethiopians still do not accept Eritrea's independence, and some writers have claimed that politicians see the loss of Badme could exact a hefty political price at the ballot box.

Eritrean officials, however, have consistently pointed out that the border ruling was based on a study of boundaries set by colonial rulers as well as arguments presented by lawyers for the two

countries.

countries.They warn that Ethiopia's refusal to respect their peace treaty and the ruling of the international arbitrators would set a dangerous precedent for other African countries that have recently signed agreements to end internal and international conflicts.

THE ROOTS OF IT ALL

Ethiopia and Eritrea were separate entities for decades until 1952, when a U.N. resolution joined them in a federation over Eritrean objections. In 1962, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie annexed Eritrea, sparking the Eritrean fight for independence.

Eritrea gained independence in 1993, but its 1,000-kilometer border with Ethiopia was never officially demarcated. The two Horn of Africa nations went to war over the border in 1998, fighting for 2 1/2 years until they signed a cease-fire and peace agreements in Algeria in 2000.

Thursday, February 09, 2006

I took a walk in the wild recently, where I hanged out with a rhino and even touched its thick hide. Although this was a relatively tame rhino, called Morani, it was still a dangerous animal - so we were accompanied by a game warden who was armed with a rifle. We all walked away with our lives and limbs intact.

The rhino is a large, primitive-looking mammal that dates from the Miocene era, an ancient period during which early humans are thought to have evolved in Africa. Nowadays, the rhino is threatened by people seeking its horn for use in

folk medicine and high-priced ornaments and jewelry, although it is not a true horn - it is made of thickly matted hair that grows from the skull without skeletal support.

folk medicine and high-priced ornaments and jewelry, although it is not a true horn - it is made of thickly matted hair that grows from the skull without skeletal support.Since 1970 the world rhino population has declined by 90 percent, with five species remaining in the world today - two of them in Africa - all of which are endangered, according to the Africa Wildlife Foundation.

My wildlife adventure also took me to a chimpanzee that quickly proved that members of the species are curious, intelligent and social - they are mammals that are most like humans.

A male chimpanzee stopped walking on the soles of feet and the knuckles of its hands when it saw humans. It stood upright and walked on two feet with great pride, and great effort, as if to say that we are no different from him. If that was the point the chimp was trying to make, then he was not far off the mark because more than 98 percent of the human genetic code is similar to that of a chimpanzee. Definitely something to think about.

A male chimpanzee stopped walking on the soles of feet and the knuckles of its hands when it saw humans. It stood upright and walked on two feet with great pride, and great effort, as if to say that we are no different from him. If that was the point the chimp was trying to make, then he was not far off the mark because more than 98 percent of the human genetic code is similar to that of a chimpanzee. Definitely something to think about.

Friday, January 27, 2006

Disaster struck at noon. Dozens of construction workers were having lunch or napping after working for some six hours at a five-story building when the structure shook and collapsed, trapping many in a concrete-and-steel tomb in downtown Nairobi.

I arrived at the site shortly after the collapse and saw hundreds of street vendors, shop keepers, the unemployed, passers by and others rush to the rubble and use their bare hands, crow bars, sledgehammers and other primitive equipment to free some of the victims from the dusty tomb.

People desperately shouted the names of friends and relatives through drainage pipes and holes cut through the concrete. A victim pushed an arm through the rubble and asked for help, saying that a colleague was pinned on the legs by a massive concrete slab nearby.

Thus began the latest man-made tragedy to hit this East African nation, in the afternoon of Monday, Jan. 23, 2006.

The disaster was a product of corruption and incompetence at the City Council of Nairobi as well as greed by owners of the ill-fated building. On day four, troops lit a memorial flame at the site to mark the end of efforts to rescue possible survivors. Rescuers will now focus on recovering the remains of anyone still beneath the rubble.

Reports allege that owners rushed construction workers to put up new floors before concrete on the lower level had set properly.

Soon after the tragedy struck, Kenyan politicians made noises to the effect that the country has learned a lot from the latest tragedy.

The insincere comments apparently tested the patience of Kenya’s Chief of General Staff Lt. Gen. Jeremiah Kianga. He made that clear when he was given the microphone at the televised memorial service Thursday.

"This is not the first time that we are learning lessons, and we cannot be students forever," Kianga said.

Relatives have named 10 people whom they said were working at the site before the building collapsed and are now missing. More than 100 people were injured in the collapse. About 280 laborers were at the site in central Nairobi when the building came down, survivors said.

In May 1996, at least 16 people when the marquee of a building housing a supermarket and a photographic studio collapsed after a strong thunderclap and bolt of lightning. It was the last major building collapse experienced in Kenya's capital city and a report of an inquiry into the building's collapse has never been acted on.

There are fears that many buildings in Nairobi either being put up or already constructed in recent years have not been properly inspected because of rampant corruption in the City Council of Nairobi.

It remains to be seen whether anything will change following the latest tragedy.

Monday, January 16, 2006

A great tragedy unfolds everyday in northern Uganda, where for nearly 20 years now residents have lived in fear of brutal attacks by the Lord’s Resistance Army – a rebel group that is notorious for abducting children and forcing them to become combatants or sex slaves. The elusive insurgents are also feared for their practice of hacking off body parts from civilians, turning them into living warnings to people not to support the government.

I traveled to the region recently to meet some of the thousands of children who trek from their isolated homes every night to take shelter in urban centers in an effort to escape the violence and possible abduction.

I also met some of the women who had their lips and ears mutilated by the insurgents and heard tales of their horrific experience.

More than 1.5 million people have fled their homes to escape attacks by rebels or on the orders of the government that is keen to deny food and support to the insurgents. The people now live in sprawling, overcrowded camps made up of conical, thatched huts, where disease and hunger kill 1,000 people a week more than would otherwise be expected to die in the region.

Doreen Aciro, above left, is a victim of the horrific mutilation. She was abducted

when she went to fetch firewood outside her camp, that is similar to the one above. The rebel commander, who was between 17 and 20 years old, then pulled out a razor blade and gave it to a 10-year-old fighter and ordered him to cut her ears and then her lips.

The cultlike Lord's Resistance Army is led by a shadowy figure, Joseph Kony, and made up of the remnants of a northern insurgency that began after southerner Yoweri Museveni took power in 1986. Its numbers are believed few, but it has thrived on creating fear. The government also has been accused of atrocities, and of herding civilians into camps to ensure the rebels find no supporters in the countryside.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)